Stories … of doubtful providence*

‘The Australian’ (5881 words)

Fictional Unity (1770 words)

… In which I unite the factions of the Australian Labor Party

My First Fight (513 words)

Expect an attack at any time …

O, Really? (1025 words)

My Greatest Creative Influence (2292 words)

“Only 15 months into the venture, his eucalyptus trees towered over him…”

Attilio the Hungry (625 words)

The White Knight of Equity (2054 words)

STORIES

‘The Australian’

At the end of 1985 I had just turned not-so-sweet 16 when my mother announced she would take the family on a holiday to Hong Kong for our summer break.

“… not-so-sweet 16 …”

My sister and I groaned in unison at this news.

We loathed Hong Kong, a destination of interminable boredom; a dirty, concrete jungle, filled with desperate beggars, strange smells, and rude Cantonese people crowded into every conceivable nook and cranny.

My 17-year old sister loved to shop but even for her Honkers held no appeal: in those days there was nothing worth buying in Honkers, unless you had a kitsch love affair with Chinglish. My mum still made me wear a t-shirt with ‘The Dating Game,’ emblazoned above a picture of a gridiron player (Perfectly good! No holes!). That attracted a few I’m-laughing-at-you-not-with-you snorts on the streets of Sydney.

Contrary to what most people thought when they saw us, Hong Kong was not home for my sister and I. We had both been born in Australia. Even if I had wanted to ‘Go back to China,’ as was so often requested of me, I couldn’t: I had never even been to China. True, I had visited Hong Kong, which is where my mother had grown up, but at the time it was not part of China but a British protectorate. (Try shouting that back at a clenched fist. ‘Take that, you ahistorical Philistine! And by the way this t-shirt is ironic!’)

Trip to Flance anyone? I hear 1914 was a popular year to visit.

Suffice to say that Hong Kong was not my spiritual home. Exhibit A: When we last went on one of mum’s Honkers holidays, I was press-ganged into Mandarin classes five days a week. Exhibit B: After said classes, my sister and I had to tag along behind our older brother as he spent our bus money on establishing his Beatles album collection. He managed to get all except Abbey Road by the end of that fateful summer, and in exchange I developed an intimate knowledge of Hong Kong’s steamy back alleys in lieu of bus routes. To this day I cannot hear the strains of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ without the smell of simmering pig’s trotters pervading my olfactory senses.

On this occasion, however, my Mum, ever the thrifty housewife, had come up with the ingenious idea to send us to a real school even though it was our summer holiday. That way we would learn real Chinese (the Mandarin I had learned from my paternal grandmother didn’t count), and she could save money, and she would be free during the days. Win/Win/Win!

If public high schools in Honkers were anything like Australian public high schools, I knew I was going to be in for a rough time.

Day 1

Mum and I sit across from the school principal. He is a neat Cantonese gent wearing a cardigan over his white shirt and non-descript tie in the universal fashion of boring people all over the World. He sits ramrod straight behind his desk, all the better to promote his 5 foot high frame.

My mother and the principal converse in Cantonese. I wait for her to draw breath and interject, ‘And don’t you think I should get a school uniform?’

My mother rolls her eyes and although I don’t understand much Cantonese, I can understand derision when I hear it in her voice as she translates for the principal.

She and I had already had this out: school uniforms are compulsory (me), school uniforms are too expensive for a mere eight week stay (her); if I don’t have a uniform I’ll be bullied and ridiculed (me), no-you-won’t-be-don’t-be-ridiculous-if-that-happens-I-just-have-to-walk-away (her). The funny thing was that during the year we had lived in the US for Dad’s work, where school uniforms were not compulsory, Mum had bought me two pairs of identical grey tracksuit pants and two red skivvies (turtle-necks) on account of my susceptibility to bronchitis. These, she announced, would be my ‘school uniform’. All the kids had wondered why I wore the same thing every day.

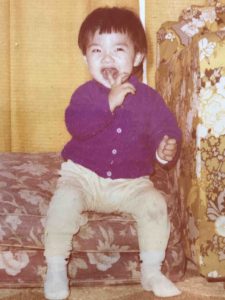

My U.S. ‘school uniform’

Now I look at the principal, willing him with my eyes to agree that Mum should absolutely get a uniform if she wants me to avoid lifelong physical and mental scarring.

The principal replies, ‘Tell your teachers that you have been exempted and that they can direct any questions to me.’

I do as I am told. My first class is something in Cantonese. There are about 40 boys in the un-air-conditioned room. The teacher barks at me in Cantonese. I don’t understand. He points at my clothes. I explain in a mash-up of Mandarin, English and broken Cantonese that I have an exemption from the principal.

In retrospect I can see the teacher’s point of view: my personal exemption from the school principal made it look like I was getting favourable treatment and it made him look silly. Couple this with the unforgivable sin of not speaking Cantonese? Of course there would be a price to pay: After-school detention.

At recess I follow the boys outside to the playground, a 50m by 50m square of concrete for 2,000 boys. Despite the cramped quarters the boys play all manner of vigorous games: Tag, Chasings, ‘Hackey sack’. The result is a cacophonous din of noise that grows deafening as the sounds bounce off the walls.

I feel trapped and try to squeeze through to a pocket of the square that is slightly less crowded. A few kids approach me out of curiosity, puzzled about how I have come to be at their school, out of uniform and not speaking their language even though I am clearly Chinese and therefore should speak Cantonese.

In that sea of kids I stand out like a sore thumb: no school uniform and four to six inches taller than most of them – all that Australian meat and three veg.

“In that sea of kids I stand out like a sore thumb …”

Across the sea I spot another sore thumb: a Caucasian boy! I make my way towards him, hoping for a conversation in my actual native tongue which, despite appearances, is English.

‘Hi.’

‘Hello.’

I give him the abbreviated version of how I ended up here. He looks at me in bemusement.

‘But you’re Chinese.’

‘Australian actually.’

‘Then you should speak Chinese!’

‘I do. I speak Mandarin.’

He shook his head. Not just confused. Afraid.

Before I can open my mouth to explain that contrary to popular belief, Chinese language ability is not a genetic trait, he has turned, his blonde hair a receding beacon in a sea of black.

Well, it’s only day one, I remind myself. There’s bound to be someone to hang out with. And indeed, just as I am thinking this, three boys approach me.

The one in the middle is about 5’5’’ and the boys on each side are larger than your average Honky, probably about my height, around 5’ 10’’.

‘You know martial arts?’ The boy in the middle asks by way of introduction.

When I was little and before my parents had separated my Dad had taught me how to trip someone and how to fall so I didn’t break my neck. Or strictly speaking, so my sister – the apple of his eye – didn’t break her neck: She needed a training partner after all. A couple of lessons on our roof with my sister was the sum total of my martial arts experience before we jet off to the U.S. As a ventolin puffing allergy-boy, my Dad thought that was about all I could handle. ‘And remember!’ Dad would warn, ‘Don’t hurt your sister.’ Of course not. She was his favourite: Trip, gently let down. Trip, gently let down…

I reply to the middle boy, ‘I know how to fall over. Sort of. But that’s not a lot of use to be honest. And what about -’

The boy glances at one mate and then the other, and they walk away.

The bell rings and I sit through two hours of scintillating lessons in an incomprehensible language.

Finally, lunch time.

The initial curiosity has worn off and no one approaches me. In true Australian tradition I cannot not tell the difference between one Asian face and another, and make a few awkward, failed attempts at identifying the boys who had sought me out earlier. Fortunately, a boy comes to me and strikes up a conversation. We are two sentences into an actual conversation when the bell rings. Still, he grins and waves as we head off and I have high hopes that tomorrow we will get to sentence number four.

I make my way to the lockers to fetch books for the afternoon’s session.

I turn around and literally bump into the three boys who had asked the cryptic martial arts question.

‘Give me all your money,’ the small one says.

‘I can’t give you all my money,’ I reply. ‘I need it for the bus.’ It’s true. I have to take two buses to get to this school and there is no way I could walk all the way in under two hours.

His henchmen lay into me with a sudden ferocity, taking me completely off guard. I am no match for their trained Kung Fu moves. I buckle to the floor. The boys continue to kick and punch me in the head and steal my wallet.

Finally the blows slow and stop. The leader says something in Cantonese which his henchman translates into broken English.

‘You give this much every day.’

I roll over and try to stand. ‘I can’t give you that much every day. Mum only gives me that once a week.’

Before I can finish my explanation the boys re-commence kicking. Then as suddenly as they appeared, they are gone.

I enter class late, bloodied and bruised, tears streaming down my cheeks. The entire class turns and stares as I ease myself into a seat.

‘Hong Yin Yerrng!’

The teacher who just mangled my name is gesturing that I must stand and come forward. He wants to know who did this to me, I think.

‘Why are you late?’

I was attacked by three boys,’ I reply.

‘Detention. Don’t be late again.’

There were snickers from the class. It was clearly what I deserved for not speaking Cantonese.

Mum meets me after school.

‘Why are you late?’ she complains. ‘I’ve been waiting for 30 minutes!’ She takes a closer look at my blood-stained shirt and red-rimmed eyes.

‘What did you do?’ She asks me accusingly.

I can’t answer that surrounded by other schoolboys who could be allied to the bullies despite being in a different year. I remain stolidly silent until we step inside the sanctuary of my grandparent’s apartment.

I sit on the floor (‘Not the couch, you’re covered in blood!’) and break into tears. The two elderly female servants that have served Mum loyally since she was a girl flee into their tiny, grubby, cubby hole next to the kitchen garbage. They can sense what is coming.

I tell Mum what happened.

‘Why did you have to go and start a fight?’

‘I didn’t!’ I exclaim but Mum cuts me off.

‘I know you! I know what you’re like!’ Pursed lips behind a shaking forefinger.

‘Can you get me a school uniform please?’

She spins around, hand already raised to strike me. I raise an arm to protect my head. She takes a deep breath, letting her hand drop, and I drop my arm too but raise it again reflexively when she suddenly yells, “You lots are always costing me money!”

My sister drags herself in a few minutes later, looking as dispirited and exhausted as I feel. She joins me in renewed pleas to go back to Australia, or failing that, to be sent to Mandarin classes like last time. Oh halcyon days of Mandarin class!

‘No!’ my mother yells at us. This is our holiday! You stay here and learn real Chinese!’ She grabs her purse. ‘Come on Hung-Yen. We get school uniform. Ah ya! Such a baby. Always having to look after you!’

The knuckle she normally aims at the top of my skull lands on my temple. I’ve grown a few inches in the last year.

*

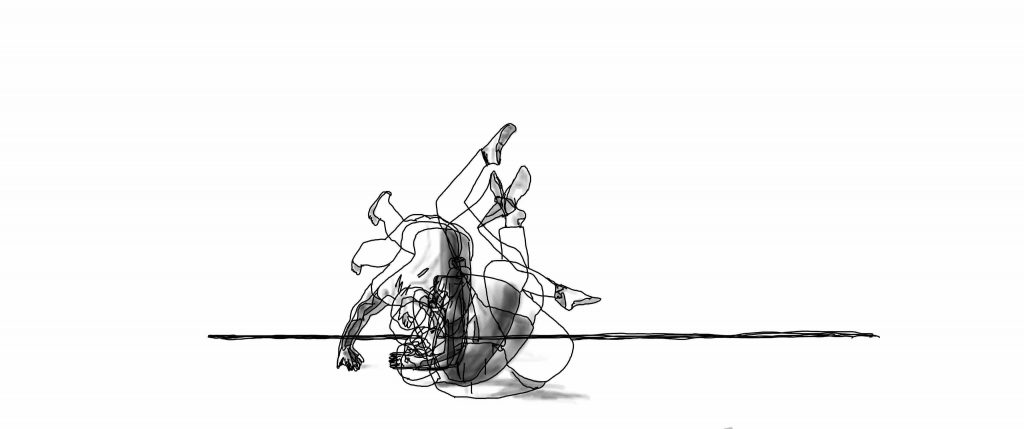

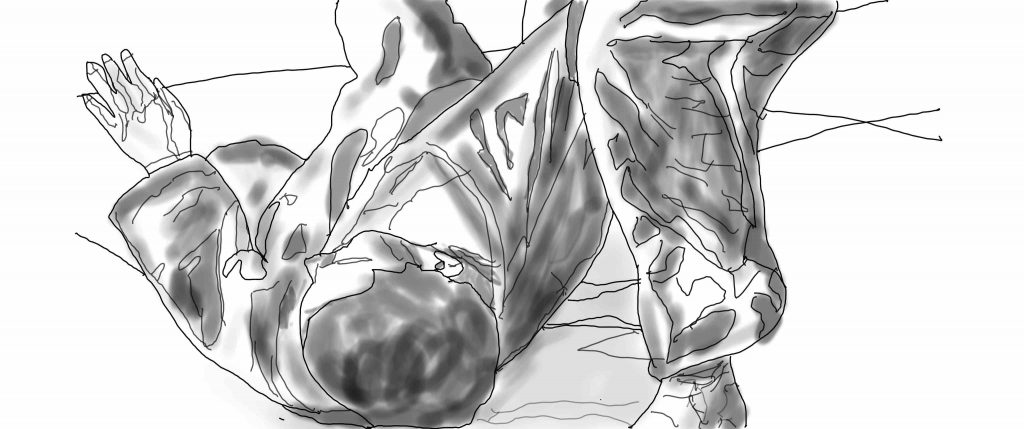

Practical Tip**: How to fall

Falling is inevitable. It doesn’t matter how big and strong you are, one day, you’re going to run into something even bigger and stronger: Planet Earth. So it’s advisable to learn how to fall with grace and the minimum of fuss. CLICK HERE to learn how.

*

Day 2

On Day 2 I make my own way to school. As I enter the school building I try to swallow my dread of seeing the bullies. Perhaps they won’t recognize me in my school uniform?

I am right. All day I am unmolested. I don’t even see the bullies. True, I am also left unmolested by any kind of friendly advances: even the boy who talked to me at lunch time yesterday must have heard about the beating because I don’t see hide nor hair of him. I don’t blame him. In Australia it’s the same. Who wants to hang out with the bullies’ favourite punching bag? That’s right: Nobody, not even the punching bag.

At the end of the day, after Detention #2, I catch the poor man’s bus, unable to stretch the few coins I scrounged off my sister to the fare for the so-called luxury bus populated by office workers.15 The poor man’s bus stinks and looks like it might fall apart in a stiff breeze, but it has the advantage of being completely bereft of my schoolmates. Even so I can’t help glancing over my shoulder every time someone sneezes. At last, after an interminable and stinky ride, I alight at the Yau Yat Cheun interchange for the last leg of my trip.16 I am the only person to get off. One more bus and I’m home free.

I stop short. Thoughts of home sink to the pit of my stomach with a thud. Across the road standing inside the bus shelter are my three attackers and a dozen of their closest friends.

The smaller boy who checked if I could do martial arts before relieving me of my week’s bus allowance is clearly the leader of the wider gang. Younger boys scurry about, picking up cigarette butts that have a few remaining puffs in them and deliver them to their overlord. Others carry food offerings from the gaggle of school girls, who giggle and whisper or drape themselves across the laps of the older boys. For a moment I am Dian Fossey observing the accepted social order and blind obedience amongst the gorillas in the mist. Except these gorillas wear school uniforms.

(Click on the picture above to start the GIF animation)

Outside school, the bullies allow themselves to really occupy their alpha male skins. The older boys smoke the proffered cigarettes, whilst the omega males fuss on the fringes in the hope that some of their idols’ “coolness” will rub off on to their attentive, bespectacled selves. The bullies lounge about the bus shelter with studied languor whilst the younger boys busily move from one bully to the next, nervous hosts at an outdoor soiree.

Leaning casually against the bus shelter wall, one leg propped up on the bench, the leader puffs on a cigarette and then throws the butt on the ground. The cigarette butt is promptly picked up and removed by one of the lackeys.

All this I observe from a distance of a mere five metres. I am frozen to the spot, my heart pounding with an unarticulated question: Fight or flight?

I could feasibly get away without them noticing. Even though I was the only one to alight from the bus19 the gang members have been too engrossed in their own social microcosm to notice me.

But my feet won’t move and it dawns upon me: They are not here by accident. This interchange is the chokepoint and these bullies are the gatekeepers. I and the other omega males must pay the daily toll before being allowed to pass: money, cigarette butts and whatever else they demand: I would belong to these boys for the next eight weeks.

And if I don’t deliver? My bruises throb as a reminder of what lies in store. These kids don’t appear to follow the Marquis of Queensbury rules of gentlemanly combat. In fact they probably learned their real Kung fu just as Bruce Lee did in the nearby backstreets: jump-kicking in the alleyways of Hong Kong’s laundry-laced public tenements. One appropriately placed kick to the head and I could leave Hong Kong in a wheelchair or worse.

Yet again I think about how hard a place this island is; how dog-eat-dog a country must be to produce boys with eyes as dead as cold fish, their greatest ambition to join older brothers in the Tri(a)d and true tradition of holding a butterfly blade to the throat of a reluctant shopkeeper who doesn’t yet realize what is good for him.20

I can’t believe how stupid I have been. Why didn’t I tell them I was a black belt? Bloody idiot, I curse myself.

And now I really have been an idiot, letting myself stand here like a statue for I don’t know how long, because the leader looks up and sees me.

‘Flee! Flee for your life!’ I think. I drop my school bag. My body starts moving like an automaton. My feet are carrying me straight towards the head bully, one leaden foot after the other.

‘Turn around and run!’ I scream internally at myself, but it’s absolutely no use. An unconscious part of me has control over my limbs. All I can do is watch in horror as my body draws closer and closer to the boy who will doubtless soon be beating me to a pulp.

I feel as though I will vomit and that my knees will give way simultaneously.

Maybe spew would turn them off soiling their shoes on my head, I think to myself. It’s the only hope I have.

Now I am planted directly in front of the leader. He eyes me as if I am an unwanted bug on the windscreen of his future.

“Whaddayouwant?” He drawls in Cantonese.

The buzz of conversation abruptly ceases. The henchmen stare at me, the piece of dirt who has caused their leader the discomfort of speaking.

My voice barely comes out a whisper and even I don’t know what I am going to say until the words are out there and I can’t get them back.

‘I’m here to fight you.’

I can’t swallow because something the size of a cricket ball has swollen inside my throat.

The bully scoffs and then ignores me, turning to his mates who follow his lead and resume their conversations as if I am not even there.

My punch ploughs right into the centre of his face, which buckles horrifically from the impact of my fist.

*

Practical Tip**: How to bunch a fist

Life getting to you? Feel like smashing someone’s face in? I won’t judge. It all starts with a simple punch. But before you punch, you have to bunch. CLICK HERE to learn how.

*

One, one thousand, two, one thousand –

The lead bully’s eyes roll up, up, up and disappear into the back of his head, leaving only the ghoulish whites looking at me.

– three, one thousand, four –

His body slithers to the ground like so much shit flung at a wall.

– one thousand, five, one thousand –

The leader’s right hand man throws a reflexive punch at my head, but because he has been taken by surprise, the blow lacks force and speed. The left hand man quickly follows suit with another punch aimed at my head and half a dozen hands grasp at me from my sides and my rear flanks.

I grab the henchmen’s punches by the wrists: fortunately for me their punches are ever so slightly asynchronous. I deflected the right hand man’s punch with my left hand and the left hand man’s punch with my right hand and used their wrists to pull the boys across me.

I do the same thing with my legs: right leg for the left bully: left leg for the right bully. Thanks for the muscle-memories Dad!

*

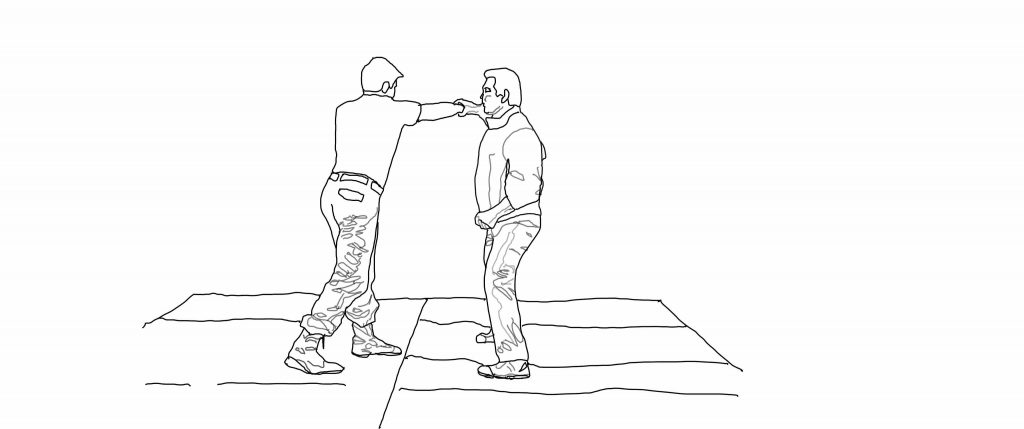

Practical Tip**: How to ‘catch’ a punch

A punch is one of the most common physical attacks. No form of self-defence is complete without a suitable response to it. CLICK HERE to learn how.

*

– six, one thousand, seven, one –

This being my one martial arts trick, a bit like Harry Potter and Expelliarmus!, I do the same thing to the assailants at my 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock. Because I stepped back to pull and trip the first two, the punches of these next two land in the empty space in front of me.

– thousand, eight, one thousand –

I rotate to catch the other boys who are standing behind me and to my right. With no time to kick, they too throw reflexive punches which I deal with in the same way.

– nine, one thousand –

Before me are two piles of schoolboys, one on my left, the other on my right. Girls and the younger boys shriek so loud and I want to cover my ears except I still need my hands.21

– ten, one thous –

*

Practical Tip**: The Pile-up

The pile-up is a good old rugby trick. If you pile boys on top of each other, then you only have to deliver the occasional punch to the top one. This prevents him from getting up and thereby keeps the rest neatly pinned under his weight. Real life ‘whack-a-mole.’

*

-and, eleven, one thousand, twelve –

I haul people up from the left-hand pile and simultaneously trip and punch the people trying to get up from the right. Soon I have successfully consolidated and amalgamated them into one writhing pile of humanity.

-teen, one thousand fourteen, one –

I consider my next steps as I pummel the top-most body. Hmmm … I still have at least three or four opponents on the loose somewhere behind me, who by now are prepared for my trip and pile tactics. They’ll start to coordinate. I have to get moving.

Only 50 or so metres away I see a familiar-looking staircase cut into the cliff-face. Could it be … Tian an lou ti? The stairs to heavenly peace, or well, to my grandparents’ place?[i]

– thousand fif-

Someone tries to grab me from behind and another tackles me from my left. The lackeys! Lucky for me, they have never played rugby and a tackle around the knees or ankles is beyond them. I keep my footing like Gulliver against the Lilliputians.

-teen, one thousand sixteen –

The other two remaining boys grab me and start furiously pounding me in the stomach with their free hands.

I tense my stomach so their punches bounce off my abdomen. I catch the nearest assailant and heave him on to the pile of groaning, flailing testosterone. Number two comes at me with a bravery beyond his station.

It doesn’t help him. I add him to the pile.

Now there are only two left. One must be a boy of only 12 or 13 years, striking at me in a frenzy of hate for disturbing the social order. The other must be the same age and has me in a body hug. I turn my full attention to him, making his sloe eyes widen like saucers. He lets go and tries to flee. I snatch at his school jumper but he wriggles and writhes because he knows his life depends upon it and shakes himself loose as the other boy continues to get in my way.

The body hugger makes a beeline for the public tenements across the road. I brush off the other one and set off after my quarry.

Adults call half-heartedly at me to stop, but no one intervenes.

I swerve and jink23 past them, dark blurs as I continue my relentless pursuit of the last boy.

He runs into the smelly, dirty apartment blocks, indiscriminately knocking obstacles in my way, I hurdle over baskets of vegetables, mops, buckets and any other detritus the boy throws in my path.

My quarry runs into a dead-end where a doughty middle-aged woman is doing her washing. She tries to stop me but I have already executed a flying rugby tackle, pinning the boy to the ground with bone-crunching momentum and driving blows through him, a bunny in my maw.

I can’t stop kicking and punching. The boy no longer moves. As if from a distance I hear the shouts of the woman, outraged at my brutality. On an island where beggars are routinely spat upon and kicked by passers-by, I have gone too far.

The woman is soon joined by other bystanders and inhabitants of the tenement. I ignore them and stoop to the boy’s back pocket. I pull out his wallet and see his identity card. In Hong Kong you have to carry this official card with you at all times or risk deportation to the mainland.[i] It’s a system of strict liability on this little island, so close to the raging yellow hordes of China. Dog-eat-dog, remember?

I have an idea. I jog slowly back to the bus stop, past the dozens of stunned adults. They fall silent as I pass. I slow to a walk and re-enter the scene at the bus shelter.

Two boys from the pile are easing themselves off and shaking sore limbs when the girls see me and start screaming again. Too late. I knock over the two boys and kick those lower down, each kick extracting a satisfying groan of pain.

I pin the escapees’ right arms behind their backs. I can feel that I have reached the natural limits of their shoulder sockets. I shove their wrists further so that their shoulders pop out, accompanied with cries of agony.

I make sure that I do their left arms as well, just in case any of them are left-handed.[ii]

I fish out their wallets, some of the boys in the pile sticking out hands and giving them to me to avoid a shoulder dislocation. The wallets bulge with bills. This gang must cover a territory much wider than my bus stop.

I take the money and their identity cards.

I bend down until I am face to face with the leader. He is lying facedown towards the bottom of the pile and closes his eyes, hoping I will think he is unconscious.

‘Tell your friends: I know where you all live.’

I flash his identity card at him.

‘If I see you or any of your friends again or if I hear of anything happening to my friends or family, I’ll come to your home and kill you and your families.”

The boy opens his eyes.

‘Did you get that?’

Still face-down he nods in furious fear, his one visible eye wide and white. He begins to yell in Cantonese and I catch occasional words. ‘Australian.’ ‘Family.’ ‘Home.’ ‘Killed’[iii]. He is translating my threat for all the gang to hear.

I walk away and pick up my school bag[iv] from where I had left it across the bus lane. I toss the wallets and identity cards into a garbage bin. I climb the stairs in the cliff-face to discover this is indeed the way back to my grandparents’ home. I walk through the park, letting this rare green oasis soak through my skin and wash away my fears.

‘How were things today?’ Mum asks.

I nod and sit down to do my homework.

*

Day 3

Day 3 begins with Hong Kong’s usual smoggy grey-brown haze.

Bus. Classes. Boring. Repeat.

It is almost recess when there is an announcement over the school’s PA system. I recognize my name amongst the Cantonese phrases. I am to go to the principal’s office. His secretary watches as I approach with as much disapproval as she can squeeze into her slanting eyes. Her hands still shuffling reports, she glares at me, then the Principal’s office door, directing me with her eyes. I amble past her.

The principal’s room seems much more cramped and crowded than it had just two days earlier.

A small Cantonese woman and her 13 or 14 year old son sit in the visitor chairs. The boy’s eyes are purple-black and puffy and half his lip is engorged. I don’t recognize him.

I take the remaining seat and calmly return the principal’s gaze. He starts immediately shouting at me in Cantonese even though he knows I can’t speak the dialect. The berating is clearly not for my enlightenment but to impress the mother of the other boy.

Eventually he stops and looks at me expectantly. The mother also watches me, worry puckering her brow.

‘Mm sick gong, mm sick tang,’28 I say. (I don’t speak or understand your language).

The principal launches into another Cantonese tirade.

I focus on the movement of the man’s lips, all the while a single fragment of Year 9 Shakespeare running through my head:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.29

Clearly, this is the idiot.

My emotions shift from resignation and indifference to contempt as I see this little man’s quivering, wet lips spout a torrent of empty and hypocritical words, trying to emotionally intimidate me.

He ends with a question that he actually translates into exasperated English.

‘Did you attack this boy?’

Recognition dawns. This is the one I chased into the dead-end.

‘No.’ I reply. Ever since I got home yesterday, I have felt an unspeakably profound calmness. It is almost as if I am no longer subject to the whims of my own body. I can watch these people going about their tawdry lives, and feel nothing.

It makes telling the truth laughably straightforward.

‘He attacked me,’ I say.

‘On my first day here I was attacked from behind by three bullies when retrieving books from my locker. They stole my money and demanded to be paid the same amount everyday thereafter. I was put on detention for being late for class despite telling the teacher I’d been attacked.

‘Yesterday I saw the bullies at the bus stop and attacked them. This one defended them, so I dealt with him too.’

Feeling as serene as the Buddha under the Bodhi tree, I glance at the boy. He bows his head, his upper body convulsing with sobs. Yes, the beating had hurt. But the truth is hurting even more.

His mother does not wait for a translation. She launches into a tearful tirade involving vigorous accusatory gesticulations. After what feels like minutes she finally pauses to draw breath, then tries to continue in the face of my utter indifference. Eventually she slows and stops mid-sentence, breaking into tears.

With his mother’s head bowed next to his the schoolboy whispers to her, eyes glancing my way then ducking back down when he sees that I am staring straight at him.

What he says startles his mother out of her sobs.

‘Gong ma yeah?’ (“What did you say?”)

He mumbles and then looks at me with pure terror writ across his countenance.

She asks me in English, ‘Where is his identity30 card?’

‘I don’t know.’ I shrug. I look at the boy and ask conversationally, ‘Hey, that reminds me… What did I say to you and all your friends the other day?’

Now I feel something: A rage like lava rising up my throat.

Before he has a chance to reply I tell him in a crescendoing hoarse whisper.

‘I said that if I ever see one of you again, or even hear from one of you again, I’m going to come to your home and KILL YOU AND YOUR FAMILY! NOW GET OUT OF MY SIGHT!’

The mother grabs her boy by the wrist and hurries out the room. She glances over her shoulder to see if I am chasing them.

I turn to face the principal. He begins to yell at me again but is cut short by my expression. I get out of my seat and feel myself tower over this man in charge of the hearts and minds of 2,000 boys. He shrinks back, his pulpit now a prison.

‘And as for you!’ I shout. ‘Who are you to stand there all high-and-mighty in judgment of me? You’re the one that’s failed EVERYBODY! Those boys beat me up and robbed me on the FIRST DAY I WAS HERE! And where were you to protect me? Your teachers did NOTHING to intervene! I was black and blue, with blood pouring out of my lip! And you know what they did? They put me on detention for being late to class! They, and you, are powerless to protect me in the playground or on the way back from school.

‘This should teach you a lesson for turning a blind eye to this type of violence in your school, and to permit a bullying culture to thrive in your school. YOU’RE the problem!”31

His lips tremble. He sees my sneer and tries to disguise his terror with outraged dignity. I ignore his shouts and head out the door.

I hear the words squeak out of the shelter of the little man’s little office.

‘You are expelled!’

The secretary watches me with all the contempt she can muster and the judgment of this person who knows nothing is suddenly too much for me. I stop in my tracks and bellow at her:

‘What are you looking at!’

She tries to pretend she is unshaken but her hands nervously toss the paper on her desk. She is still picking up dropped reports as I turn on my heel and leave.

*

Practical Tip**: How to trip

There are few pleasures in life quite as satisfying as using your opponent’s own force to make them fall flat on their face. The trip is the first of many useful ‘take-downs’ every martial artist should have in her repertoire. CLICK HERE to learn how.

*

I don’t remember much about how I got home. I can recall the feel of the sunlight through the bus window on my face which had a smile creeping across it for the first time in three days.

‘What happened?!’ My mother yells when I enter with my four hours (and seven weeks and two days) early mark.

I reply, ‘I am not going back to that school. It’s not safe for me there.’

My mother stares at me. I stare back.

Finally she spits.

‘And I spent all that money on your school uniform.’

I reach into my pocket and fling a fist full of cash in front of her.

‘Here’s your money.’

Two days later I am on a flight back to Australia. At Sydney airport the customs officer directs me to the line for international visitors. I point to the kangaroo on my passport cover and try to explain to the man-just-doing-his-job that I am home.

I think to myself, at least there’s one island in the world where I will forever be known as ‘The Australian’.

[i] There were wall-to-wall public announcements about the importance of carrying your identity card with you at all times on all of Hong Kong’s TV networks. All I can find now is some of the more tame, administrative stuff: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V6TcTupiHDg ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6AMY8vW5wVg

[ii] I’m normally terrible with details. My wife says my form-filling ability is ‘remedial’. But when it comes to things like this …

[iii] The Cantonese word for ‘killed’ is so final. It’s said with a rising intonation: ‘Sei’: http://www.cantonese.sheik.co.uk/dictionary/characters/446/

[iv] A khaki Army Disposal Store backpack that had been handed down to me from my older brother.

[i] It had been five years since I last climbed those steps, and even then, I had come from a completely different direction.

Fictional Unity (Work in progress)

In which I unite the factions of the Australian Labor Party

I finished high school in 1987 and not knowing what else to do, enrolled in a law degree at the University of Sydney.

The campus was awash in nascent political fervor.

At the time, John Howard was shouting from the rooftops that the immigrants were to blame for all of Australia’s woes. Howard and his conservatives ran about, busily demonizing people who looked like me. This was after two decades of compassionate, bipartisan policies welcoming Vietnamese boat people.

But now it is the 1990s and after 11 years in the political wilderness, the conservatives are desperate. They turn to the only Anglophone conservative government they respect – New Zealand doesn’t count of course – and adopt the winning tactics of the U.S. Republican Party. The secret formula? Oppose everything. Don’t announce any policies, and let the opposition unbalance itself and trip into the policy void. Pick up on anything the public likes. From this populist soup, the long-suppressed head of xenophobia rears its head again.

I am not especially political, but when good friends of mine join the Young Liberal Party I have to do something. They are sons of immigrants like me, but their parents are pasty white, whilst I am the colour of delicious buttermilk (or cream-gone-slightly-off, depending on which side of politics you align yourself with).

I will show them. I decide to join the Australian Labour Party. I don’t know much about them except that they are theoretically the opposite of the Liberals who are now anti-immigration, anti-people like my parents. Like my grandmother.

I ask around at university and am told to come along to a Young Labour meeting in my local area, Hurstville, a south-western suburb of Sydney.

I enter the hall where the meeting is being held. There must be more than 100 people in here, all blokes wearing what seems to be an unofficial uniform of charcoal grey trousers and white business shirts. I look down at my faded sports t-shirt and torn jeans and double check the sign but I am in the right place: Young Labour, 6.30 pm.

A tubby little Greek Australian breaks away from his huddle and approaches me.

‘What are your views on unions?’

The smaller guy starts yelling at me. He misquotes my feelings that they had an important part to play in developing an egalitarian society, but can abuse their power from time-to-time.

“This guy HATES unions!” He is screeching at the top of his voice. Heads turn towards us.

I can’t get a word in to correct him, so I shrug. ‘Yeah, whatever mate.’

I am tapped on the shoulder. Behind me stands a strapping, Anglo-Celtic Australian bloke with shoulder-length brown hair. He must be at least 6’2” and looks as though he is a rugby league forward stuffed into business attire.

‘Yeah this is the guy! He hates unions!’

The moonlighting rugby forward shoves me. What’s going on? I wonder in surprise.

I don’t have time to ruminate. Guys can sniff out a fight like dogs can smell a bone. Several blokes come over from one of the groups in the room and join in with the shoving.

I am still managing to deflect most of their shoves when the big guy throws a punch at me. All I do is defend myself: I am studying law and very aware that any infraction would prevent me from being admitted to the NSW roll. One wrong move and I might have wasted six of the dullest years of my life.

But, I reason rather desperately as the number of assailants swell to five, a punch is pretty clearly something that I can legally use force against, as long as it’s in ‘proportional self-defence’.

I deflect the rugby gorilla’s punch and knock him out. Two of the others start trying to pummel me but I beat them to it. I’m faster than they are which is the one thing saving me from a bloody nose or worse right now.

Not everyone knows this, but speed can be learned.

Untrained fighters will tend to ‘telegraph’ their punches, and so my fist can be across their jaw before their fists are more than halfway towards mine, even when they are the ones to throw the first punch. This is something a kung fu mate of mine taught me and which I am now applying with the sort of acumen that can only be born of need.

In most fights, if you fight off the first two or three, the rest runaway. But these ALP guys just keep increasing like heads on a pustulant hydra. I knock down three; three more replace them; white-sleeved arms grasp at me from left, right and behind; still more barge me.

This entire environment is hostile. I need to do whatever it takes to get myself out of here.

I punch and kick everyone and everything within range. By now there are about 12 guys trying to form a solid circle of brawn around me. It’s just a matter of time before they have me hemmed in, making me a sitting (Peking) duck.

In situations with multiple attackers I tend to choose the biggest, most aggressive opponents; when you take them down, the morale of the rest of the group tends to take a hit even if they outnumber you.

I take a running jump at the largest, scariest looking guy in the closing circle. The wind whistles past my ears as I fly through the air.

Crash!

The two of us topple together on to the hard wooden floor. His chest cushions me because his lungs are full of air which the weight of my body knocks out of him. I scramble up, only to find myself surrounded again. A wall of young men stalks towards me on one side and another wall on the other side. I don’t recognize any of these guys from the original altercation. ‘I have done it!’ I think irrelevantly. I have achieved the Left’s Holy Grail of uniting the factions of the Labour Party in a common goal. Unfortunately, that common goal is not industrial relations reform, but to beat the living daylights out of me.

Since I started university I have been practicing tae kwon do, which consists of

marching up and down gyms with wooden floor boards, doing kicks and punches in the air. Tae kwon do has its failings but it has trained me perfectly for this situation.

I feel the pinch of my “good” black court shoes. I hate these shoes: too often they have given me blisters at 3.00 am after a student party, wandering Sydney’s deepest, darkest Northern Suburbs – that’s where all my other Law School friends live – in search of the last taxi on earth. But right now, they are exactly what I need.

You rarely see a kick above waist-height in a street fight for good reason: an opponent can easily dodge or catch your kick, or your momentum can leave you off-balance and very vulnerable to a counter-strike.

The only way to keep your balance in a reverse turning kick is to spin your head at 360 degrees as fast as you can, waiting for the rest of the body to ‘catch up’ like a ballerina doing a rather ugly pirouette.

The ring of men around me tightens. It’s now or never. I spin into a reverse turning kick and watch my rock-hard court shoe heel smash half a dozen jaws, their owners collapsing like a row of skittles.

I have cleared the wall of people on one side! But I don’t have time to enjoy the martial arts movie montage of my actions because I have to regain my balance before someone takes advantage of my vulnerable position. I use my momentum toskip over the prone bodies behind me. I turn to face the approaching wall, putting the tangle of bodies between me and them.

The wall pauses at this obstacle.

‘Anyone who steps forward gets the same,’ I say with as much menace as I can muster.

The men hesitate for a fraction of a second. Even though they outnumber me by about 20:1, I can almost see the thought flicker through each man’s mind: if I am the first to get into that Chinese guy’s range, I’m going to cop it.

In their moment of hesitation I flee for the exit.

Metres from the door I hear hard footsteps on the floor behind me. I look over my shoulder and sure enough, a group of about four or five guys is chasing me.

“If anyone follows me, I’ll kill ‘em!” I scream.

The guys skid to a halt, arms akimbo in comical chicken wing postures like kids losing a game of musical statues.

I wait until I have reached the Hurstville Post Office on Forest Road, about 100m down the hill from the meeting hall, before I slow down to a walk and “blend in” with the crowd of office workers on their way home from the train station. This is harder than it looks, as Hurstville has not yet undergone its ‘Asianisation’ into a suburban Chinatown. The foot traffic is seventy percent Anglo-Celtic, twenty five percent ‘Mediterranean’/’Slav’.

I have only walked a few metres when I hear someone shout, ‘Wait! Wait!’

I swivel to see two white-shirted people charging down the hill, weaving their way through the other pedestrians on the footpath. ‘Seriously?’ I think, more exasperated than angry. I am exhausted. Can’t they just let me go?

One of the pair is the little guy who had started this whole debacle. Sure enough, the other is his trained gorilla. He has blood running down his nose on to his formerly pristine white shirt.

I stalk back up the hill to meet them. The adrenalin that fuelled me has deserted me and my body feels like a soggy, wet sack of potatoes. I remind myself that it’s moments like this that you just have to dig deep. Bullies don’t exactly wait for you to feel your best before they strike.

I raise my fist but my screaming muscles beg me to try a verbal bluff first. ‘I said I’d kill anyone that followed me!’

The big fellow backs off in terror, holding up his hands in surrender. The little fellow has just caught up with us and shouts, ‘No, no wait! Don’t hit us!’

I sneer at the little bloke. “Give me one good reason.”

Still clutching his knees to catch his breath, he looks up at me with excitement written across his eager face. ‘We could really use someone like you!’

Suffice to say, the only cards I carry to this day are for the bank and the library. Factional unity still eludes the Labor Party to this day.

My First Fight

(Work in progress)

PRACTICAL TIP**: Expect an attack at any time. Attacks will come out of nowhere: always when you least expect it; always when you least want it. That’s why they’re attacking you.

My first memory of fighting was with my older sister. Still in our little house beside Mount Ousley Road, I don’t think I could even walk at the time it took place. A slow walker, I was probably around 18 months old when the incident took place, which would have made my sister 3 and a half – more than double my age.

Left: My sister, aged 3.5 Right: Me, aged 18 months

I remember playing happily in the lounge room, when all of a sudden, a sharp pain came from my head. My head had been yanked by the hair, and I caught a glimpse of my sister’s face, set in a mean grimace, angered by what I didn’t know. It all seemed so unfair.

When she did not let go, despite my wailing and screaming, I instinctively grabbed a lock of her hair, and I still remember hanging on through the intense pain: my pudgy little baby hands with a tuft of her black hair sticking out between the thumb and forefinger of my fist, clinging on as if my life depended on it. She didn’t let go. And neither did I. We kept this up, both of us screaming and crying by this stage, and neither of us willing to let go. I don’t remember who did what first, but I remember a clump of her hair coming away from her scalp as I kept pulling. She saw her hair and screamed even louder at the realisation she’d lost a part of herself. It was only then I saw the tuft of my hair that had come away in her little clenched fist. She grabbed another tuft of my hair, and I hers. More tufts were lost.

Eventually, it was my grandmother that separated us. She tried to understand the origin of it, but my sister and I were both bawling so loudly for so long, I don’t think any of it was intelligible to her.

Later, when I had calmed down, my grandmother asked me again, and I told her: “She started it, but I don’t know why.” My grandmother consoled me by admitting she also thought my sister had started it. The reason was obvious to us. Even though my sister was my father’s favourite, she was still jealous that I was my grandmother’s favourite. My blithe happiness was an insult to her jealousy.

Years passed and my sister would occasionally speak to me of the bald spot on her head that she blamed on me. It was only when we were both in our thirties, that I realised she was talking about this hair-pulling incident which she herself had started.

PRACTICAL TIP**: Life is unfair. Deal with it practically. Don’t expect life to be fair. Thinking and feeling you are hard done by won’t solve anything. Deal with life as you find it, in practical actions towards your goal.

O, Really?

It was probably in Kindergarten, that I got into my first serious scuffle – discounting the innumerable one-to-one encounters I had already faced. Meaning ‘more than one assailant’, at the age of 5, my definition of ‘serious’ was already beyond the threshold of what most Australian adults will experience their entire life.

My school uniform handed down from my 6-year older brother. Fits perfectly!

It is a sunny day. During the lunch break, I am looking for four-leafed clovers; who doesn’t want 7 years good luck? The grassy playground has numerous clumps of clover and whilst stooping to pick some, I am suddenly tackled to the ground. I am surrounded by five towering second graders who all begin to kick me as I lie on the ground blinking at their scowling heads like cut-outs on the bright azure sky. Dressed like all school bullies, their shirts are untucked and dirt stained, their shoes scuffed.

Back in those days, school shoes were not the sensible, supple sneakers I just bought for my daughter for her first year of kindy. In the mid-70’s, uniforms were still modelled on the 19th century British Public School uniform: itchy, too hot for the Australian climate, and hard, black court shoes that were a gaol for feet that had run around bare all summer. I coveted the most popular brand: the Bata Scouts which all the boys loved because it had a compass concealed in the heel.

From my worm’s eye view I could see the Bata Scouts up-close and personal: the scuffed square toes of Bata Scouts come whizzing straight at my eyes and into my soft 5 year-old body. I cover my head with my arms, begging them to stop. The boys kick and chant:

‘Go back home Ching Chong Chinaman’

‘We won the war, in 1974. They showed their guns, we showed our bums in 1974!’

‘Go back home reffo.’

But I’m not Chinese, am I?1

What war in 1974?

Aren’t I already home?

The kicking continues.

I close my eyes, praying to the God my six-year-older-brother-tells-me-doesn’t-exist-so-it-must-be-true, but the kicks keep coming. A thought crystallizes through my pain and confusion: These guys aren’t going to stop!

Practical Tip**: The kicking will never stop as soon as you want it to.

I battle through the blur of tears and pain to gradually push myself up off the ground. I tense my core muscles to reduce the pain of each blow to my body and shield my face so the kicks directed to my vulnerable skull won’t hurt quite as much. The kicks keep raining down.

On my feet now, but still doubled over, I can see out of the corner of my eye that the 2nd graders have formed a neat wall from which they all shove and jeer at me. Their kicks now land on my shins and ankles, fortunately already desensitised2 and bruised3 from our inept five year old attempts at soccer during recess.4

I twist my body and sink a fist deep into the closest boy’s soft belly. He promptly collapses with an, ‘Awwww.’ I remain bent in a turtleback against the incoming blows and shuffle along the wall to hit the next boy. Same thing happens. Now I unfurl myself and straighten up to see the third boy looking at me with eyes and mouth open wide. Before I can punch him, he turns and flees. The other two boys are already meters ahead, the lion paw print soles of their Bata Scouts winking at me as they tear down the soccer field. I swivel to deal with the first two boys but they have also upped and run. I give chase, screaming, arms outstretched. But they are too fast, and before too long my undiagnosed asthma stops me in my tracks, huffing and puffing, hands on my knees.

I stagger back up the hill to find a teacher. Tears and snot drip down my sobbing face.

There is Mr O’Realy, only a few metres away. He has a reputation amongst the boys as the toughest disciplinarian on the staff. He stands, legs apart, pale yellow short sleeve collared shirt, broad pizza-patterned tie, socks pulled right up to his knees, and khaki ‘drill’ shorts with his tan-brown leather shoes. Of all the teachers, he’ll know how to sort out those boys.

I crane my neck up, look past his crossed, hairy, sunburnt forearms, to see halcyon blue sky behind his ‘combed-over’, balding, ruddy dome.

Tears still in my eyes, I cry, “Sir, Sir! Those boys just tackled me and kicked me to the ground!”

He turns his head slowly down in my direction, pretending to notice me for the first time. This is it, I think. He’s going to ask me which ones and they are BUSTED.

“See this line here?” I follow his pointing finger, craning to see what he is talking about, but try as I might, I can’t see a line: only tussocks of grass and clover as far as the school fence.

“You crossed it. You shouldn’t have been playing in the second graders’ area.” Mr O’Realy re-folds his arms and acts like I am no longer there. Mr O’Realy has taught me a lesson I will retain with me throughout my life.

PRACTICAL TIP**: In life you’d best learn to look after yourself. No one else will.

1 It was only later that year that I teased my sister for being a Ching Chong Chinaman. She said ‘Mum’s a Ching Chong Chinaman, so you’re a Ching Chong Chinaman too!’ Quietly she added, ‘We’re all Chinese.’ Disbelieving her, I ran to my mother to find out the truth. ‘Mum, are you Chinese?’ Still facing the stove that she resented, she grumbled, ‘Ye-eess’. I was stunned and barely squeaked out the next question. “Does that mean I’m Chinese?” (Even grumpier) “Ye-eeesss’. So there it was. I was ‘Chinese’!

2 Practical tip: Pain-tolerance is nine-tenths of fighting.

3 I remember in first grade counting more than 27 bruises on one shin alone.

4 Wollongong had many of the waves of post-War European immigrants described earlier. So although rugby league was the main game, played in the morning before school and at lunch time, a concession was made for soccer to be played during recess.

My Greatest Creative Influence

(Work in progress)

On my first day of film school, we were broken up into groups of about five students, each group paired with a teacher from the school acting in the role as a facilitator.

The following is my story from that exercise.

As we went around the small group and others told their story before me, I racked my brain to think back who it might be. I took my cue from others in the group: My mother? She likes to draw. My grandmother? She’s very special to me. A favourite teacher?

When I finally opened my mouth, I was surprised to hear myself say: ‘My father is my greatest creative influence.’

I found it strange to say that, because my father and I had never particularly got on. In fact until a rapprochement two years earlier, I had actually hated my father, to the point where, as a kid, I had resolved to never be like my father.

For one thing, he had an explosive temper. Growing up as a boy in Wollongong, my memories of that time was that, like clockwork, every day after he got home from work, I’d cop a beating. It’s probably because I was being very naughty – I don’t know. What I do remember thinking at the time though is that ‘He doesn’t understand me.’ And over time, I guess the thought that ‘He doesn’t understand me’ combined with all those beatings morphed into the sentiment: “He hates me.”

This was in stark contrast with the treatment of my sister who was older than me by 2 years. Contrary to the myth that all Chinese families revere their sons, especially their eldest son – that was my older brother by six years by the way – the apple of my father’s eye was my sister. She could do no wrong.

Of course, all of this discrimination was just accepted in my family. My sister was my father’s favourite; my brother was my mother’s favourite, and I was my grandmother’s favourite. It’s just the way it was in our family, and we were all quite open about it.

So this was another point of differentiation: I abhorred injustice. I had crammed my Combined Law degree with subject choices like Moral Philosophy, Retributive Justice, Distributive Justice, Sociological Jurisprudence, The Law of Human Rights … You get the picture.

I remember one big fight I had with my Dad in my university years, was over whether I got to live in the family ‘boatshed’. The ‘Boatshed’ was actually a granny flat that was down the front of our property that fronted onto the Georges River. It was a family rite of passage for my brother and sister years earlier when they entered university. A rite of passage, that is, until I came along. And even though my sister had moved out two years earlier, leaving the place like something out of the last days of Pompeii, my father insisted I leave it vacant ‘in case she returned.’ Against his screamed protestations, I moved in anyway.

Another example of the sort of thing my father did was typified by the time he came home after being overseas for a year. I was 13 at the time and very excited to see him. We met him at the airport, and besides his usual luggage, he had a brown cardboard box, about the size of my grandmother’s Singer sewing machine box, taped and tied up with that blue, flat, nylon string you get.

At home I asked him what it was – not expecting it to be a present for me, because I knew my Dad. He said, ‘Oh, it’s a computer.’

This was exciting news, because personal computers were ‘the latest thing’ in 1982.

‘Who for?’, I asked. I mean my brother was in Med school at university, and he didn’t need one. And my sister hated computers. At that age, in Year 9, she had fallen in with the ‘make-up set’:- the ‘glamour girls’ of her high school who were already in TV commercials and concerned themselves with nothing more than looking pretty.

‘It’s for Martin.’

Martin was the eldest son of our closest family friends, the Fang’s, from down the street in Wollongong – ‘the other Chinese family’ as we liked to say because in Wollongong during the 70’s, it felt like there were only our two Chinese families. Martin was my age, in the same year at high school, but his parents had sent him to Sydney Grammar, despite the 2 and a half hour commute it meant for him – each way, every school day.

A few years later, I was spending the summer with the Fang’s, and I asked Martin, ‘What motived your father to buy you a computer?’ He cocked an eyebrow in surprise, ‘My father didn’t buy it for me. Your father bought it for me.’

One should bear in mind that it was 1982 when my father bought that computer for Martin, and computers cost around AU$2-3,000 at the time. With inflation being what it was then – in double digits – we’re talking about something that was probably around $8-10K in today’s money. This generosity to others was in stark contrast to what he spent on us. Though ‘asset rich’, in typical Chinese fashion, we lived like paupers, with ill-fitting school uniforms and hand-me-downs. Toys were only something my sister got on these homecomings from my father, my brother (besides being too old for toys) having been showered with gifts from our extended family on account of his being the oldest boy of the oldest child on both sides of the family.

Around 3 years later, Dad finally bought me a computer. And around 10 years after that, I belatedly learned that he hadn’t even actually wanted to buy that computer for me. What had happened was that my grandmother found out about the gift to Martin, and quietly suggested my father get me one too. My grandmother was the polar opposite to her hard-charging, visionary, short-tempered son; a stereotypically tiny, quiet, humble, Chinese grandmother. She nevertheless knew just the right button to push with my father. When he refused to buy me a computer, she had threatened to buy me one out of her meager pensioner’s savings. Embarrassed into buying me a computer, the next thing I know, on one of his return trips, my father belatedly brings me a computer.

So besides Dad’s bad temper, neglectful parenting and plain favouritism, the other aspect of Dad that I sought not to emulate was his career. He was an engineer. He had trained as a mechanical engineer at Sydney University, and whilst finishing his PhD at UNSW and raising 3 kids, and working full-time at the steel mill, and building our enormous four storey house in Keiraville, he finished an electrical engineering degree through night courses.

One day, when I was around 3 or 4 years old, Mum took me in to pick up Dad from work. Dad worked at the steel mills in Port Kembla. I only found out 30 years later when he was bragging to my fiancée that it was ‘The First Computerised Steel Mill in the Southern Hemisphere’. The foreman at the mill, derisively nicknamed it ‘F.R.E.D.’ which stood for ‘F**king Ridiculous Electronic Device’. It was to save the mill a fortune.[1]

So we drove into Port Kembla, from Keiraville, which in those days was lush, green paddocks with cows and horses grazing in them.[2] As we got closer to Dad’s work, the air began to darken with visible filth and we would wind up the windows of the Ford Cortina station wagon in ritualistic fashion. Even before we got to the steelworks, its unnatural, acrid stench had permeated our nostrils. Everywhere one looked was a rusty, hulking building with chimneystacks, belching out flames and smoke.

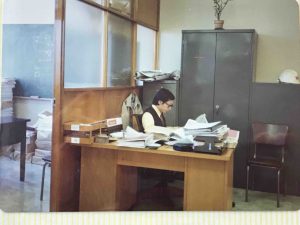

When we finally got into Dad’s work place, we entered a cavernous room, around twice the height and three times the size of the nearby University gymnasium. In this room/man-cave there were neat rows of hundreds of desks, a meter apart: row upon row, column upon column, like a physical manifestation of an Excel spreadsheet. Most desks were deserted, I’m assuming now because Dad liked to work late. Those few who remained were all men. As I passed each desk, I was just tall enough to glimpse what was on each one: Slide rules were ubiquitous; retractable pencils, templates with funny shapes on them.

We finally reached Dad’s desk where he was hunched over. He noticed us and his face brightened at the sight of my sister: ‘Welcome to my work, darling!’

I had known deep inside me, from the moment we’d entered that room, that I never wanted to be an engineer.

In the years to come, Dad’s ‘projects’ took him further and further away from us, for longer periods of time, until, essentially from the time I was in Year 7 in 1982, we only saw our father around 2 weeks in the year.

During that time, I had entered university, not knowing what I wanted to become. So I did a Combined Law degree to make sure I covered all bases. After stumbling my way through a Law degree in which I felt I never belonged, and working as a solicitor for a year, I had to admit to myself, Law was not for me.

I bumbled around like a lost soul in the private sector for a few years. A new breed of Asian Underachiever I finally landed a job that the recruiter had told me no-one had wanted despite months of advertising. It was in statistical software sales. I promptly broke sales records that had stood for over 13 years. These achievements even brought me to the attention of the US-based CEO I would discover whilst playing him in a game of pool. Understanding statistics and people was easy for me, but it wasn’t satisfying. In four short years, I announced my ‘retirement’ just before my thirty-second birthday. Checking with the numerous mathematicians at my workplace, I had saved enough money to theoretically last me until my dotage should I choose to be frugal.

Nevertheless, I found myself at a crossroads again. A few weeks before I left my job, I bought the career-guide classic, “What color is my parachute”. I concluded from it that I would be happy in anything that had the following attributes. Things that were:

- Original

- Visual

- Involved the synthesis of ideas and application of these into the real world

- Collaborative

- And gave back to the community

As soon as I left my job, I immersed myself in conceiving, then orchestrating and running a film project that took into account the Internet: Mini Movie Moguls (MMM). I dubbed MMM the ‘World’s First Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Film Competition’. Four teams of filmmakers made 16 film ‘segments’ – short films that ended on a cliffhanger. Each round, one segment was chosen as the winner, and the teams would continue on from that film segment’s cliffhanger.

A year later, I was accepted into the prestigious Australian Film Television Radio School (AFTRS). In those days each student – and there were only 64 in a year – received a stipend of around $15,000 p.a. That’s right. We were paid to make films. 🙂

Just before entering film school – only a couple of weeks before I would be asked the question ‘Who is your greatest creative influence’ – I bumped into my father on a visit to my mother’s apartment. He was on a rare visit back to Australia. Of course, he had not come to visit family. He was looking for investors in his latest scheme. He excitedly showed me photos as he outlined the grand plan: Fast-growing eucalyptus trees.

I rolled my eyes.

In the intervening decades since Dad’s job at the steel mill, he had gone out on his own with the following ventures: a pioneering venture into energy saving lamps which he patented and set-up the factories in China (another ground-breaking thing at that time, being the early 80’s); farms out near Dubbo which had failed at everything from ‘Pawlonius’ trees to Chinese musk deer, to emus to … eucalyptus trees. Suffice to say, each of these business and farming ventures had failed. Yes. My father had even failed at growing eucalyptus trees. In Australia.

Now he was trying to grow eucalyptus trees in China. To his credit, the photos he showed me revealed he was onto something: Only 15 months into the venture his eucalyptus trees towered over him, around 12 meters high.

But I had to shake my head and ask in an exasperated fashion.

‘What motivates you to do all these crazy things Dad?’

He paused and thought for a moment: “Well, I guess I just like to do things that are original. Things that are technical – use my engineering brain. And things where you collaborate and give back to the community.”

My jaw dropped. Unprompted, he had said four of my five criteria.

It was as if a shadow had been cast over me and I had looked up to see a huge stamp falling on me: Whoomp!!! And a voice from the sky had boomed in an echoing baritone, ‘You are your father’s son!’

My greatest creative influence is my father.

[1] It was, in fact, so successful, they commissioned him to design a new, bigger computer, which took up even more room than the small-room-sized precursor. They then dubbed the old one ‘Little F.R.E.D.’, and the new one ‘Big F.R.E.D.’

[2] It has gradually been consumed by the nearby university, and paddocks have been converted into car parks, student housing, etc etc.

Attilio the Hungry

I am in second grade and every day I get a lift home with my mate, the other Chinese[1] kid in Mount Ousley Public who also happens to live on the same street as me. Martin Fang and I dawdle through the school playground up the slope to the rear gates where Martin’s father picks us up after school in his beaten up, boxy little Fiat 124.[2] I am pretending to go through the gears, like the Fi as it struggles up Mt Ousley Road.

Suddenly out of the corner of my eye, I see a body hurtle itself at Martin, tackling him to the ground. A split second later, the world tumbles about my head, green grass switching places with blue sky. It’s Trevor Cole. He is one of the second grade tough kids, a bead of sweat and a smudge of dirt always upon his dark face. He straddles me and starts punching. Desperation makes me wriggle, buck and grab his shirt front, and I manage to swing him into the ground to my left. In an instant I am astraddle Cole and ramming fists into his face. He pleads for me to stop, but first I have some questions.

“Why (punch) did (punch) you (punch) do that (punch, punch)?!”

Speaking in his husky whisper from behind his hands, Cole replies, “‘Cos you didn’t give us any Twisties[3] at play lunch.”[4]

I stop punching.

“But I didn’t have Twisties at play lunch!?”

“Ohhhh. Must have been the other Chinese kid then.”

I hastily glance over at Martin, only to see his face being pounded repeatedly by Attilio Pirozzi. I immediately leap off Cole and shove Pirozzi away from Martin. I attack Pirozzi with my kiddy punches until he too pleads for mercy. I push off Pirozzi and hover above my fallen comrade.

Martin still has his forearms crossed over his face in a futile prayer. The same adrenalin that made me struggle and shove until I got loose has made my mate curl in upon himself like a fern, paralysed and just waiting for the storm to pass over to someone else’s backyard, his fighting spirit as elusive as the Borneo tiger.[5] ‘Fang’ by name, fangless by nature I guess.

‘Marty! Marty! Are you OK?’

I prise away Martin’s arms to reveal his face: It is shiny red from tears streaming down his cheeks, his face screwed up in silent anguish.

Soon afterwards, for Dad’s work, my family moves to America for a year. Upon our return our first reunion with the Fang’s is Martin’s 9th birthday party. We arrive just as the boys have surrounded the birthday cake to sing ‘Happy Birthday’.

But before the cake is cut, Auntie Pang, Martin’s mother, has an announcement to make in her sing-song Malaysian accent:

‘Martin’s best friend would like to make a special toast to Martin lah.’

Plastic cups of Fanta are raised high as I clear my throat.

‘To Martin!’

But it is not my voice. This time Attilio has beaten me to the punch. He and Martin beam their big moon faces at each other. Attilio and Martin are best friends.

PRACTICAL TIP**: Don’t try and reason with the unreasonable. You can waste a lot of precious time trying to work out the reasons a bully is attacking you. By the time you’ve even finished asking the question, you may have lost the fight. There’s no point in trying to reason with bullies. Bullies will always have a reason for bullying you. Just don’t expect it to be a reasonable reason.

[1] Well … Malaysian Chinese. Same, same but different lah: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_and_Malaysian_English_differences .

[2] Mum had convinced the Fang’s to do this long after Mum had recovered from a car accident.

[3] http://apgsd.com/uncategorized/new-story-o-really/

[4] Morning recess.

[5] https://news.mongabay.com/2016/11/was-borneo-once-a-land-of-tigers/

The White Knight of Equity

It is the early nineties. Sydney University Law School has a building right in the heart of the legal district across the road from the Law Courts Building that houses the NSW Supreme Court and the Federal Court of Australia.

I step out of the Law School into a cold, overcast day. Winter. There is a pedestrian crossing that runs directly across the road to Queens Square. Forget the Sydney Opera House, or Uluru: this zebra crossing is probably Australia’s most photographed location and not because of the legal profession’s good looks, but because high profile barristers, judges, plaintiffs and defendants are always being hounded by photo journalists as they hurry across the street. Think of it as the legal profession’s Abbey Road. Strawberry fields forever, as long as you have the certificate of title.

Today the pedestrian crossing and Queens’ Square are practically deserted.

Normally I turn left as soon as I emerge from the law school towards the subway.

Today my head is in the clouds of legal blah blah which I just ingested and without thinking much about where I am walking, I cross the street.

It is a fateful decision.

I have a million things on my mind – or really just one: Equity. This is the branch of the law that sits in parallel to the common law, to reduce some of the Law’s more ass-like tendencies. If you have ever studied law you will remember the famous ‘white knight of equity,’ destined to act the chevalier and save the innocent from the gnashing cogs of ‘procedural justice’. It is propounded through the impenetrably thick Jacob’s Equity textbook, made of over a thousand, rice-paper thin pages, in 6 point font.

Muttering to myself choice insults I could direct Jacobs’ way, I do not notice the two men sitting on a park bench about 5 meters from the crossing.

Not until, that is, I catch a glimpse of a blurry grey movement: Something big. Something hulking. Something smelly.

Simultaneous to the grey blur in my peripheral vision, a tall, lean blonde man jumps in front of me. He is wearing a bright red, flannelette shirt in much better nick than my winter wardrobe consisting of a faded flanno I had purchased for the princely sum of $12 at Gowings two years earlier. My affluent law school friends think I’m trying to ‘do’ Grunge. I’m just broke.

I keep looking, head down, at the meter-square pink paving. No point in letting them know I am aware of their presence. But the grey mass on my right is nearly upon me and I have to look up to see what this thing is, seemingly coming straight at me.

It is some 150 kilos of hulking brawn, wrapped in a filthy trenchcoat and scarf. He is the source of the smell. His right fist is bunched and low, but rising sharply towards my face in a ‘good ol’ fashioned’ ‘haymaker’.

The rest of his body has almost thumped into mine when it suddenly stops, then drops. The assailant’s head has run into my outstretched right fist.

His skinny mate looks stunned as he turns his head to see his fallen comrade. So stunned that he doesn’t notice that I have closed the two meters between us and make a left jab to his chin. I cross with my right, just catching the point of his chin as he staggers back, arms and legs forward like the apes that ride Harley Davidsons.

I flick sharp jabs at the lean blonde but miss. He has somehow scuttled backwards out of range. No matter. The tip of my right Doc Marten boot arcs into his ribcage with a resounding crunch. I guess I have broken one of his ribs – perhaps several.

As he falls, my right foot is on the way for a second helping. I flatten my foot to catch him with my instep. Kicking someone in the head with the hard toe of a 8 hole Doc Marten can kill a man. He who seeks Equity must come with clean hands. Or clean boots in this case.

The kick does not connect crisply, but glances off his face with a dull slap. That’s actually good. Balance of probabilities from the perspective of a reasonable man denied. Also, that should do him for a bit.

Spinning 180 degrees from the momentum of my turning kick, I am now facing the grey assailant. He is on all fours, snorting, like a bull. He spits racial epithets at the ground, as he tries to heave his considerable girth back onto his feet.

I throw punches to the back of his head. His arms buckle and he falls face first into the hard, pink paving.

I have to act quickly, as I haven’t yet knocked out the tall one. It would very soon be two against one again.

I descend on the big guy who is still cussing in shock at my initial blow.

He’s too heavy and I don’t have enough time to flip him over. I instead settle for sitting on his back and tap out a rhythm on the back of his skull, his head a speedball for my fists: onetwoonetwoonetwo–

He goes limp. I am trying to flip this lump of lard over so I can re-arrange his facial features when I notice the gangly guy approaching me. He is clutching his left side.

I spring off Fatty and address Skinny.

‘Come closer and you’ll get more where that came from.’

The blonde puts up his one good arm in surrender and backs off, still simpering in pain through gritted teeth.

I return my attention to the big guy who is beginning to peel himself off the ground.

This time, after a quick tap (OK, more like a full-blooded hook to his jaw. What are you, a lawyer?), I shove him over and grab his meaty, filthy, left hand which has been raised instinctively to protect his face.

Perfect, I think to myself.

I seize his fingers, twisting his arm back behind him. Rolling instinctively to avoid the racking pain in his shoulder, his body defies his momentum and rocks back over so he is now lying on his back.

I finally have the luxury of thinking: How dare this guy just try and jump me right before the hallowed Halls of Justice! Didn’t Jacobs’ say, “The Court helps he who helps himself.”? Probably not.

I am still hitting the bloke on the ground when the skinny guy limps up to me. I glare at him from my position atop the belly of the whale.

The uninitiated frequently think that this is when the blood begins to pour out of the guy’s skull, but that moment is at least a minute off.

His flannelette mate backs off. I return to my business, but again the blonde comes up to me, I notice in direct contravention of his natural instinct for self-preservation. Somehow overcoming his inner-coward, he shouts at me from the safety of 3 meters.

“Hey, can you go easy? He’s really hurtin’!”

I sneer at him, enough to make him back off again. He winces with each blow I land on the big guy’s head.

The skinny guy’s distraction means I only glimpse what my fists are doing in the interim: Half a dozen frenzied blows land on the big fellow. His eyes roll up into his skull, leaving the whites on duty. Somehow, his body huddles instinctively, and he rolls onto his side, where I deliver more blows.

One, one thousand. Two, one thousand.

My savagery has now truly broken its flimsy harness, and I cannot stop myself when … a sound, first soft, then increasing in volume comes from the husk beneath me:

‘Mu-u-ummy!’

I can’t believe it. Could it be?

I flip the big fellow over by his left shoulder, and out of the grey and pink mess surfaces a tear-streaked, unshaven man’s head.

‘M-uu-u-uu-uuu-mmy-hee-hee!!!’ the big fellow sob-screams.

I am in second grade. I have just fought off Trevor Cole and Attilio Pirozzi.

I pull away my mate, Martin Fang’s, forearms which have been shielding his face in fear of more blows from Attilio the Hungry. Revealed is Marty’s scrunched up face, shiny and red with tears, jaw clenched in silent anguish.

‘Please help him! Please mate. He’s really, really, hurtin’’

I look up and see the blonde guy’s face, painted in horror at the fate of his mate.

I look down at the face below me, scrunched up in anguish.

I raise my hand, but a force holds it in place, cocked next to my right ear.

A hoarse voice says, “Make yourself useful. Pick him up.”

It is me speaking.

I get off the big fellow and offer the one limp arm of the big fellow to the skinny fellow. The skinny fellow blinks in fear and confusion.

“Well you don’t expect me to carry this putrid bag of shit all the way to the hospital do you?”

His feet don’t move.

“C’mon, get over here before I chase your white arse all the way down Macquarie St.”

At that he comes forward and attempts to pull his mate up off the ground, but even this is too difficult for his one good arm. So I rudely grab the scruff of the big fellow’s shirt and yank him up with one fist gripping his curly hair. Or at least I assume that’s what his chest hairs look like beneath his shirt.

The big fellow’s torso lurches forward, almost tipping his face back into the ground. This time I catch a scruff of the hair on the back of his scalp.

“Upsa Daisy”.